Technical Analysis of PSP Investments’ 2022 Responsible Investing Report

Summary

PSP announced its first Climate Change Strategy in April 2022, and followed up in November with its 2022 Responsible Investment Report, TCFD Report and a Green Asset Taxonomy white paper. This is a big step forward for PSP in managing the significant climate risks facing its portfolio. Unfortunately, the Climate Change Strategy is missing several important and required elements.

The Strategy includes:

New investment targets for climate solutions

Target to reduce holdings of “carbon intensive assets” by 50% by 2026

Target to reduce emissions intensity of portfolio by 20-25% by 2026 (from 2021 levels)

A ‘“Green Asset Taxonomy” that defines what PSP considers to be “green” and “transition” assets

Significant increases in emissions reporting

Clearer expectations for external fund managers

Improved scenario analysis, including the use of 1.5°C pathways.

It doesn’t include:

A science-based emissions target (e.g. net-zero financed emissions by 2050)

Acknowledgement of the impact of PSP’s investment decisions on the climate crisis

Disclosure of how PSP’s existing assets are categorized under its Green Asset Taxonomy

Action to address the problem of carbon lock-in in its portfolio

Evidence supporting the use of questionable climate solutions (e.g. CCUS, offsets, and fossil-based hydrogen)

Reporting on scope 3 emissions in its portfolio-- a key metric of climate risk exposure

Clarity on climate expectations or enforcement actions for external fund managers

A credible explanation for how exactly company engagement can achieve climate action

Realistic assumptions for financial risk if we fail to achieve global climate targets.

Introduction

PSP Investments (Public Sector Pension Investment Board, or PSP) is the $230 billion pension manager for over 900,000 active and retired employees of Canada’s federal government, including federal public servants, the RCMP, and the Canadian Armed Forces and Reserve Force. PSP’s 2022 Responsible Investment Report, released on November 10th, demonstrates that PSP is responding to calls from beneficiaries for increased disclosure of how it’s handling climate-related risks and putting in place the building blocks to execute its Climate Change Strategy.

In April 2022, Canada’s fourth largest pension plan announced its inaugural Climate Change Strategy, which included new targets for investments in climate solutions, a commitment to reduce PSP’s holdings in risky carbon-intensive assets by 50% by 2026, a short-term target to reduce the emissions intensity of its portfolio by 20-25% by 2026 below a 2021 baseline, and a Green Asset Taxonomy that attempts to categorize PSP’s assets according to their readiness to transition to global net-zero emissions by 2050. PSP’s 2022 Responsible Investment Report includes an update on the progress PSP has made since April and was released in conjunction with two other climate-related documents:

PSP’s 2022 report to the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)

A whitepaper on PSP’s Green Asset Taxonomy (GAT), entitled Advancing Climate-Aligned Portfolio Management.

A close read of these documents shows that despite clear and laudable signs of progress, PSP is still falling short, including by:

Choosing not to set a net-zero financed emissions target, which bucks a positive trend in the Canadian pension sector and removes a key framework for transparency and accountability;

Acknowledging that climate change exposes PSP’s portfolio to systemic risks, but then neglecting to recognize that PSP’s investment and asset management decisions can influence the pace and scale of how big those systemic climate risks get;

Disclosing significantly more details about its green and transition assets and Green Asset Taxonomy, but choosing not to disclose where its own assets fall within that taxonomy;

Acknowledging the problem of carbon lock-in, but continuing to allow its privately-owned companies to lock-in carbon by building new fossil fuel infrastructure;

A lack of clarity on what role false climate solutions like “low-carbon fuels”, carbon capture and sequestration, and fossil-powered hydrogen will play in PSP’s climate strategy;

Significantly increasing the proportion of assets reporting emission data, but opting not to include Scope 3 emissions;

Outlining clearer ESG expectations for external managers, but making those expectations vague on climate and having no repercussions for external managers that don’t meet expectations;

Focusing on engagement of fossil fuel producers without explaining how engagement delivers climate-aligned results;

Significantly improving scenario analysis, including two 1.5°C pathways, but then concluding that PSP can deliver on its mandate in a world that warms by 4.3°C.

Read on for Shift’s highlights and analysis of PSP’s Responsible Investment (RI) report and climate-related documents.

Still no net-zero target

PSP has again missed an opportunity to set a high-level target to achieve net-zero financed emissions by 2050 or sooner, opting instead to “(use) our capital and influence to support the transition to global net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050” (RI report, p.4). This dodging of a real commitment sets PSP apart from its peers in the Canadian pension sector, eight of which have committed to net-zero emissions by 2050 and one (Ontario’s University Pension Plan) that has committed to net-zero by 2040. Net-zero commitments on their own are inadequate to achieve climate safety and protect the retirement savings of beneficiaries, but they provide a transparent framework to guide investment strategy and accountability for pension stakeholders. We remain hopeful that PSP will further clarify its climate commitment and join its peers in making a net-zero financed emissions pledge.

“Systemic Climate Risk”

PSP makes regular reference to “systemic climate change” and “systemic climate risks” in its updated RI reporting, including:

“Environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, including systemic climate risk, are some of the most significant drivers of changes in today’s world.” (RI Report, p.2)

“As a pension investment manager and asset owner, we invest and manage assets today to help meet pension obligations decades into the future. This horizon shapes how we view risks and opportunities, and compels us to consider the material ESG issues, including systemic climate risk, that can impact long-term value.” (RI Report, p.6)

“We believe, based on IPCC’s scientific evidence, that climate change is a long-term systemic risk that will likely have a material impact on investment risks and returns, across different sectors, geographies and asset classes.” (TCFD Report, p.2)

“Unfortunately, the short-term effects of systemic climate change are already being felt around the globe and are manifesting as extreme weather events. Moreover, the IPCC 2022 Report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability concluded that the negative impacts of climate change are more widespread and severe than expected.” (TCFD Report, p.4)

“In general, for all climate scenarios considered, investors should expect lower returns as compared to a world in which systemic climate change does not exist given that both physical and transition risk are likely not fully ‘priced-in’ by financial market participants.” (TCFD Report, p.8)

“A key objective in developing the PSP Investments Green Asset Taxonomy was to design a pragmatic framework to helps (sic) us to better understand our baseline exposure to systemic climate risks and opportunities across our investment portfolio, and to aid us in identifying potential ways to steer our engagements with portfolio companies (where appropriate) toward more relevant decarbonization opportunities.” (GAT whitepaper, p.4)

It is encouraging to see PSP recognize the unique, extraordinary, systemic nature of the climate crisis as something that must be considered in its investing strategy. But it is not yet clear that PSP is responding to “systemic climate risks” with the scale and urgency required to fulfill its legal obligation to provide retirement security for plan members.

Half-baked acknowledgment of portfolio climate impacts

Because of its massive, diversified global portfolio, PSP faces a crisis of “double materiality” when it comes to climate risk: its assets are exposed to climate risks while its investment decisions simultaneously influence the pace and scale of decarbonization and the transition away from fossil fuels, thereby contributing to how severe climate risks will become. PSP goes part-way to acknowledging double materiality in its RI report, saying that “Through our actions, we can also promote positive change on pressing social and environmental challenges, and contribute to a more inclusive, equitable and sustainable future” (p.2). PSP also says that “As a global investor, PSP Investments can play a significant role in the transition to net-zero emissions by the way we invest and the way we use our influence. Within the context of our mandate, we are aligning our investment and engagement strategies to support the achievement of this global goal” (p.11). And PSP claims that “By investing in key sectors and progressive companies around the world, and by using our influence to promote sustainable business practices, we enhance the long-term returns from our investments and help create a better tomorrow – for our beneficiaries, society at large and the environment” (p.16) This falls short of real recognition that ensuring its members’ retirement security requires PSP to invest in a way that actively reduces the likelihood of emissions trajectories that lock-in and accelerate “systemic climate risks.”

Investments in “Green Assets”

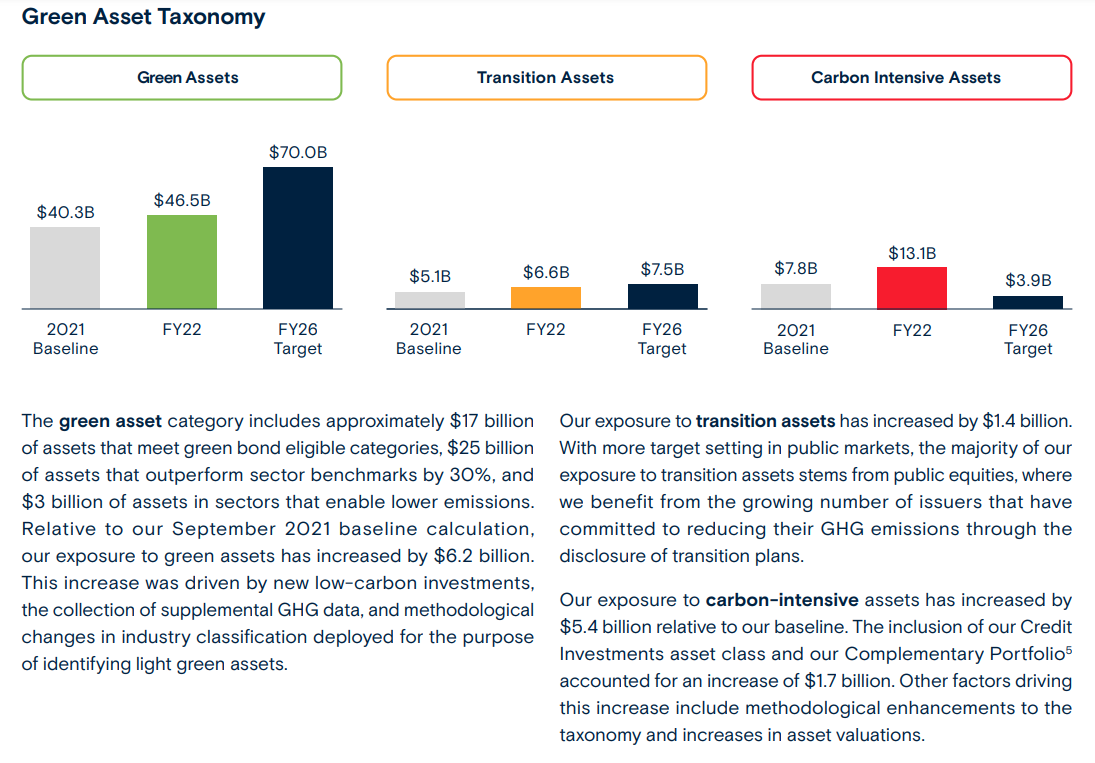

PSP reports that $46.5 billion, or 20.2% of assets under management (AUM), are “considered to be green assets” and $6.6 billion, or 2.8% of AUM, are “considered to be transition assets” (RI Report, p.8). PSP defines green assets as “investments in low-carbon activities that lead to positive environmental impacts” and transition assets as “investments that have committed to make a substantial contribution to the low-carbon transition through the establishment of public targets and disclosure practices” (RI Report, p.8). But PSP has not provided a full inventory of these assets or why they are classified as “green” or “transition”. Despite the definitions and details provided in its Green Asset Taxonomy whitepaper, PSP has not disclosed where its assets fall within its own taxonomy. For beneficiaries and stakeholders to understand how PSP is assessing and managing climate risks, PSP must show where its assets fit within the GAT, and why.

PSP highlights its majority stake in Angel Trains as an example of its commitment to climate action, noting the railway company’s efforts to remove all diesel-only trains from the UK rail network by 2040, procure electric trains, and invest in emissions-reduction hybrid technologies (RI Report, p.17). PSP also highlights its co-ownership of FirstLight Power as an example of good climate governance, noting the New England-based renewable energy and energy storage company’s strong management of climate risks and commitment to accelerate the decarbonization of the electric grid (RI, p.19).

These are good examples of PSP-owned companies investing in a safe climate future, but PSP’s RI report is noteworthy for investments that it omits– particularly its 50% ownership of TriSummit Utilities, which owns and operates fossil gas distribution and transmission pipelines in Alberta (APEX Utilities), British Columbia (Pacific Northern Gas) and Nova Scotia (Heritage Gas), as well as wind and hydro power assets in B.C. A month after the release of PSP’s climate strategy in April 2022, TriSummit announced a deal to acquire ENSTAR, Alaska’s largest fossil gas utility, which includes nearly 6,000 km of fossil gas pipelines and a 65% stake in the Cook Inlet fossil gas storage facility. The role of electric trains and renewable energy in a safe climate future is clear, but the role of fossil gas infrastructure is dubious, as the production and use of fossil gas must diminish rapidly to avoid “systemic climate change”. By neglecting to mention a credible, science-based transition plan for TriSummit Utilities in its RI Report, PSP is leaving plan members in the dark about these risky, carbon-intensive fossil fuel assets.

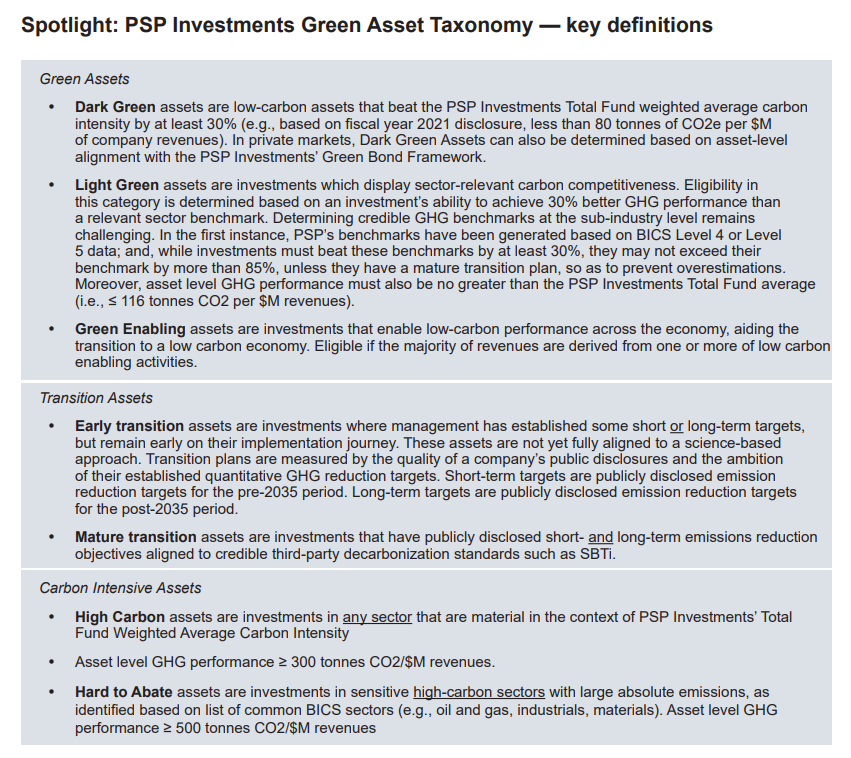

Green Asset Taxonomy

PSP provided further details of its Green Asset Taxonomy (GAT), indicating that the GAT “considers the two key variables of climate investing – carbon intensity and the credibility of a company’s climate transition plan” (RI Report, p.12). PSP says “A key objective in developing the PSP Investments Green Asset Taxonomy was to design a pragmatic framework to helps us to better understand our baseline exposure to systemic climate risks and opportunities across our investment portfolio, and to aid us in identifying potential ways to steer our engagements with portfolio companies (where appropriate) toward more relevant decarbonization opportunities” (GAT p.4). PSP says it has also used the taxonomy to “screen investments” and inform its climate investment decision-making at the asset, asset class and portfolio level.

PSP considers more than $202 billion of its portfolio, or 87.6% of AUM, to be “in-scope” for classification using its GAT, including public equities, real assets, private equity, credit investments and its complementary portfolio. Of that 87.6%, PSP has used scope 1 and 2 emissions data to map just over half ($110 billion) using the GAT, while the other $92 billion of in-scope investments could not be mapped because these companies don’t yet disclose GHG data. PSP says it intends to include scope 3 emissions data “once a sufficient amount of this information exists” (p.13).

PSP provides the following breakdown of its investments using the GAT (RI Report, p.13):

Image: PSP 2022 Responsible Investment Report. Investing for a better tomorrow. (November 2022). p.13.

The information disclosed by PSP is insufficient in allowing plan members and stakeholders to understand PSP’s exposure to climate-related risks. Firstly, the value of in-scope assets disclosed by PSP under its taxonomy in the above excerpt adds up to $66.2 billion, well short of the $110 billion PSP claims to have mapped.

Secondly, it is still not clear which companies and assets in PSP’s portfolio are “green”, “transition” and “carbon-intensive”, despite the additional definitions provided by PSP in its GAT white paper. PSP defines “light green assets” as those that outperform sector benchmarks by 30% and that “emit less than 80 tonnes of CO2e per $M of company revenues” and “green enabling assets” as “investments in products or services that enable climate mitigation and adaptation, aiding the transition to a low carbon economy. For this category, assets would be eligible if the majority of their revenues are derived from one or more low carbon activities” (GAT, p.6). PSP does not specify what a “majority” of a companies’ revenues are or what a “low-carbon activity” is. The GAT also classifies “carbon-intensive assets” as “investments in high-carbon assets or sectors that fail to show quantifiable low emission performance”, including “two sub-categories: High Carbon, whose carbon intensity, regardless of sector, is more than twice the PSP Investments FY21 Total Fund weighted average carbon intensity; and Hard to Abate, whose assets are in high-carbon sectors and whose carbon intensity is greater than 500 tonnes of CO2e per $M of revenues” (GAT, p.6).

Image: PSP Investments Green Asset Taxonomy: Advancing Climate-Aligned Portfolio Management. (November 2022), p.12.

Thirdly, PSP’s exposure to “carbon-intensive assets” increased by $5.4 billion in FY 2022 relative to its 2021 baseline. PSP explains that this increase is due to the “inclusion of (its) Credit Investments asset class and (its) Complementary Portfolio… methodological enhancements to the taxonomy and increases in asset valuations.” But in its 2022 annual report, PSP provides little information about the assets in its credit investments and complementary portfolios, making it impossible to understand what caused such a large increase in PSP’s “carbon-intensive assets”.

Finally, Shift is concerned that PSP is not on track to achieve its target of reducing portfolio emissions intensity by 20-25% by 2026 and halving its carbon-intensive assets by 2026. The 2026 emissions target is itself weaker than some of PSP’s peers, such as the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (45% below 2019 emissions by 2025) and Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (60% below 2030 emissions by 2030). PSP’s 2026 target also means that it will still be exposed to nearly $4 billion worth of high-risk carbon-intensive assets four years from now, exposing the portfolio to the potential for significant losses as the energy transition accelerates.

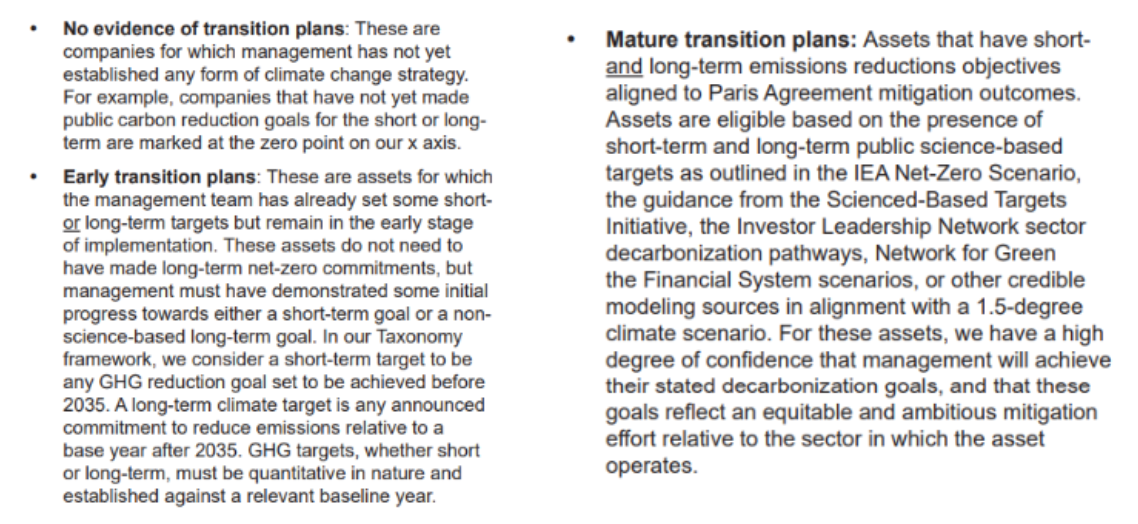

PSP provides additional transparency about its GAT by categorizing companies’ transition plans as “no evidence”, “early transition” and “mature transition” (GAT, p.8).

Image: PSP Investments Green Asset Taxonomy: Advancing Climate-Aligned Portfolio Management. (November 2022), p.8.

PSP also notes that it intends to evolve its assessment of transition readiness based on other financial metrics, including allocation of capex where relevant, and focus its engagement on outcomes like developing Paris-aligned climate strategies, setting science-based emissions reduction targets, improving board oversight of climate risks and opportunities, adopting and implementing TCFD recommendations, and “ensuring companies have a business model consistent with net-zero emissions and an effective transition plan to achieve this by 2050.” (GAT, p.8). This is welcome progress, but will only become meaningful once PSP’s forthcoming time-bound climate escalation policy, scheduled for the end of 2023, is put in place (GAT, p.8).

PSP Investments Green Asset Taxonomy: Advancing Climate-Aligned Portfolio Management. (November 2022), p.10.

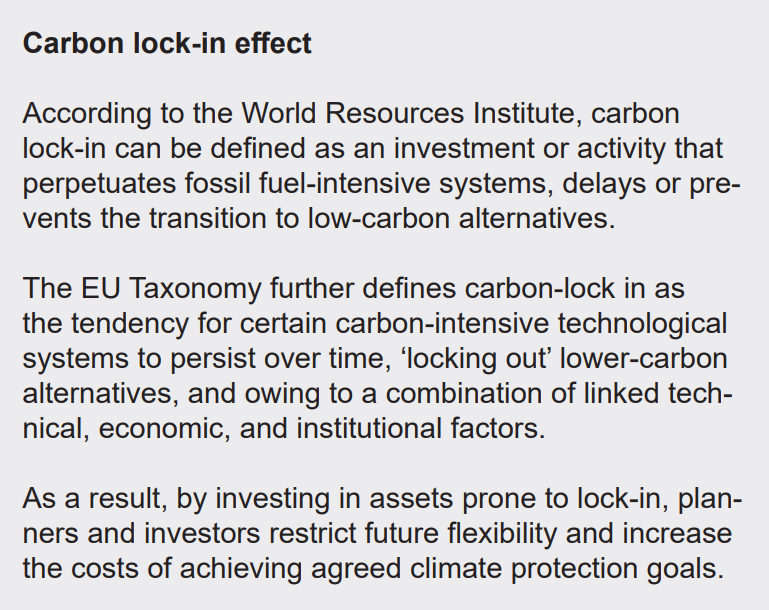

Acknowledgment of carbon lock-in

Shift is encouraged to see PSP acknowledge the carbon lock-in effect in its GAT white paper (p.6).

Image: PSP Investments Green Asset Taxonomy: Advancing Climate-Aligned Portfolio Management. (November 2022), p.6.

But it is inconsistent for PSP to acknowledge this effect without a plan to phase out assets that lock-in carbon. If PSP is concerned about lock-in, it must acknowledge that every single oil and gas producer in its public equity portfolio is planning to develop new reserves, allocate capex to expansion, lobby to weaken and delay ambitious government climate policy, and squeeze every last drop of profit out of its production capacity.

Furthermore, PSP’s assets are attempting to lock-in carbon as we speak. TriSummit Utilities’ subsidiary in Nova Scotia, Heritage Gas, is focused on expanding its gas customer base in the Halifax area, which it calls an “opportunity to capitalize on the gasification of Nova Scotia and provide clean energy to thousands of new customers.” In a July 2022 podcast, Heritage Gas CEO John Hawkins said he supported lifting a ban on fracked gas expansion in Nova Scotia, planned to expand and prolong Heritage’s gas network, and convert oil heating to natural gas heating. Similarly TriSummit’s subsidiary in British Columbia, Pacific Northern Gas, is proposing to spend $60 million to upgrade its existing fossil gas pipeline, the Western Transmission Gas Line, to add an additional 400,000 cubic metres of fossil gas per year and feed two new proposed LNG facilities in northwestern B.C. The LNG facilities would then condense the gas into liquid form and sell it to remote communities and mining operations in northern B.C. or export it to Asia. As part of the expansion project, Pacific Northern Gas also wants to build two new compressor stations and reactivate four that are not in use.

PSP is acknowledging the risk of carbon lock-in, but then allowing its companies to lock-in more carbon.

Climate Investing Themes

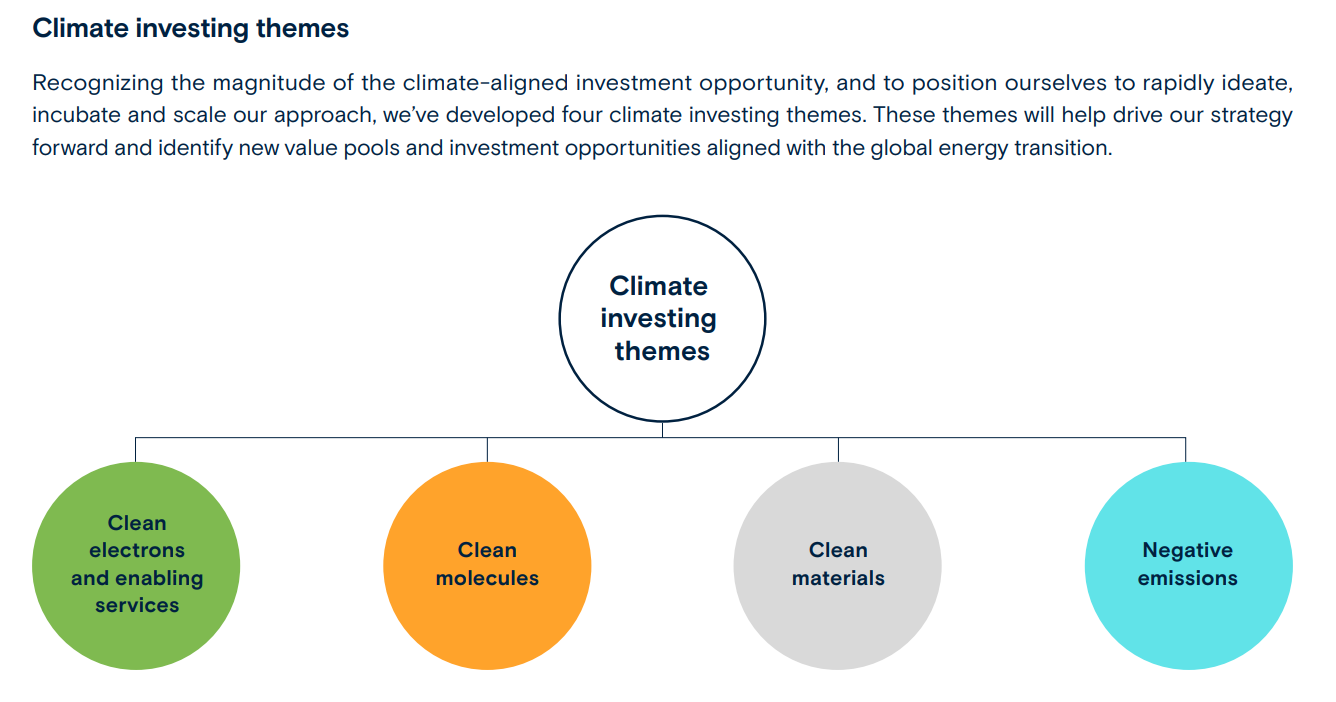

Shift’s concerns about the GAT are elevated by PSP’s identification of four “Climate investing themes” (RI, p.14)

Image: PSP 2022 Responsible Investment Report. Investing for a better tomorrow. (November 2020). p.14.

PSP’s focus on “Clean electrons” for the global power sector and electrification of buildings, transportation and industries appears to be aligned with both profitability and credible sectoral decarbonization pathways, as does its focus on “clean materials” and recognition of the need to invest in the decarbonization of materials essential to modern society, such as steel, cement, chemicals and critical minerals. But PSP’s focus on “clean molecules” and “negative emissions” raises red flags.

PSP specifically mentions the production of hydrogen without differentiating between fossil-based hydrogen and hydrogen produced from renewable energy. PSP also notes that its focus on “low-carbon fuels will leverage and extend the economic life of existing fossil fuel infrastructure.” Limiting global temperature increase to 1.5°C requires fuel-switching, electrification and the early retirement of fossil fuel infrastructure, not investments in expensive, unscalable, unproven technologies that extend the use of fossil fuels. PSP must clarify its approach to hydrogen, “low-carbon fuels,” carbon capture and sequestration and fossil fuel phase-out if its climate plan is to be credible. Similarly, Shift is concerned about PSP’s emphasis on negative emissions technologies. While these will be necessary to help achieve the 1.5°C goal in the very long term, they run the risk of under-delivering emissions removals at scale, prolonging the use of fossil fuels, and failing to be profitable when competing against existing, scalable climate solutions. PSP must clarify that investing in a safe climate future must prioritize fossil fuel phase-out and decarbonization in the short-term, with unproven negative emissions technologies playing a limited role in certain hard-to-abate industrial sectors with no alternatives in the long term.

GHG reporting and Portfolio Carbon Footprint coverage

PSP reports that 42% of its portfolio carbon footprint now comes from company-reported GHG data, a 14% increase relative to the previous year. PSP also enhanced its internal efforts to collect climate-related data from portfolio companies, a critical first step to developing its climate strategy and setting climate targets (RI Report, p.9). PSP reports that it has increased company-specific GHG data to 56% of the investments mapped under its GAT, aiming to obtain company-specific data for 80% of the portfolio by 2026 (GAT, p.13). This is a necessary step in managing climate risks and decarbonizing the portfolio, and PSP is demonstrating laudable progress.

For the first time, PSP Investments is disclosing its portfolio’s financed emissions, based on recommendations from the TCFD and informed by guidance from the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) (TCFD Report, p.11). This is another example of PSP improving its disclosure and management of the emissions resulting from activities that are financed through its lending and investment portfolios.

All of PSP’s GHG reporting continues to exclude scope 3 emissions, which are an essential indicator of PSP’s exposure to climate-related transition risks. Like other Canadian pension funds, PSP provides an explanation for excluding scope 3 emissions, citing issues with their comparability, coverage, transparency and reliability (TCFD Report, p.14). PSP also recognizes that “emissions reductions unlocked across a company’s value chain due to the nature of their product or service is a vital and often underdiscussed aspect of climate investing” and is “motivated to actively contribute to the development of methodologies that avoid potential double counting effects” (GAT p.13). While Shift appreciates the challenges associated with scope 3 data, this cannot be an excuse for inaction. Every year that PSP fails to assess and disclose climate risks associated with scope 3 emissions is a year that the climate crisis worsens and that those risks accelerate. At the minimum, PSP should look to the efforts made by Ontario’s University Pension Plan (UPP) to publish an assessment of its portfolio’s scope 3 emissions from oil, gas and mining. If the $11-billion UPP can do this, surely the exponentially larger PSP can as well.

ESG Assessment for external managers

PSP unveiled a more detailed assessment framework for external investment managers, outlining clearer expectations and processes to manage climate risks (RI Report, p.31). It also assessed the ESG integration practices of its external managers and general partners, characterizing firms as “Leading, Active, Needs Improvement and Just Starting, with regards to the robustness of its ESG practices.” PSP notes that 59% of its external managers and general partners are signatories to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, 87% have adopted a firm-wide Responsible Investment or ESG policy, and 63% have dedicated ESG staff or committees/working groups (RI Report, p.32). While it’s encouraging to see PSP taking steps to improve the ESG practices of external managers, its engagement of these firms is notably vague on climate. PSP also communicates no repercussions for external managers and general partners that don’t live up to its weak expectations.

Image: PSP 2022 Responsible Investment Report. Investing for a better tomorrow. (November 2020). p.31.

Engagement, Investment Restrictions and Divestment

PSP provides a laudable example of its stewardship of a plastic packaging company to assess material ESG factors, manage climate-related transition risks and demonstrate strong emissions performance against an industry benchmark, resulting in the company getting a “light green” classification under PSP’s Green Asset Taxonomy (RI Report, p.26). This is the only example that PSP gives in explaining where a portfolio company is categorized under its GAT.

PSP also describes its efforts to engage a chemical company that resulted in commitments to prioritize climate change at the company’s 2021 annual meeting, improve the energy efficiency of its operations, establish a net-zero goal, set science-based scope 1 and 2 2030 emissions reduction targets, and procure 50% more renewable energy by 2030 (RI Report, p.28). PSP also committed to better communicate its climate-alignment expectations to portfolio companies and work with partners to encourage the adoption of credible decarbonization plans and TCFD disclosures (RI Report, p.29). These are signs of progress in PSP’s engagement program, although they aren’t accompanied by timebound escalations like voting against directors or divestment within a prescribed period. Shift is encouraged to see that PSP has committed to develop a “Climate escalation policy” to “determine how and when it may choose to escalate its engagement with public issuers, where appropriate, and private portfolio companies if progress is not made on climate change commitments” (GAT p.8).

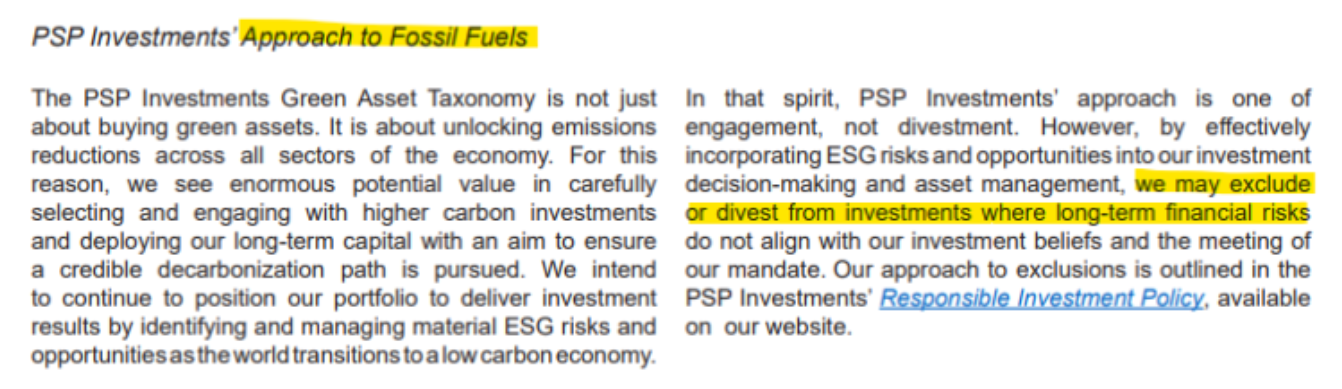

We are pleased to see PSP open the door to fossil fuel divestment in its 2022 RI Report. It noted that “We may also exclude or divest from investments where long-term financial risks do not align with our investment beliefs and the meeting of our mandate,” using its divestment of Russian assets as an example (RI Report, p.24). PSP also includes its “Approach to Fossil Fuels” in its Green Asset Taxonomy White Paper (p.12).

Image: PSP Investments Green Asset Taxonomy: Advancing Climate-Aligned Portfolio Management. (November 2022-), p.12. (Highlights added).

It is difficult to understand why PSP considers the long-term financial model of oil and gas producers to be aligned with its mandate, or how engaging such companies can bring change to a business model that is fundamentally incompatible with climate safety. PSP provides no examples of how engagement has led fossil fuel companies to phase out production, retire assets early, or reallocate capital to renewable energy, which are their only credible, profitable pathway to decarbonization.

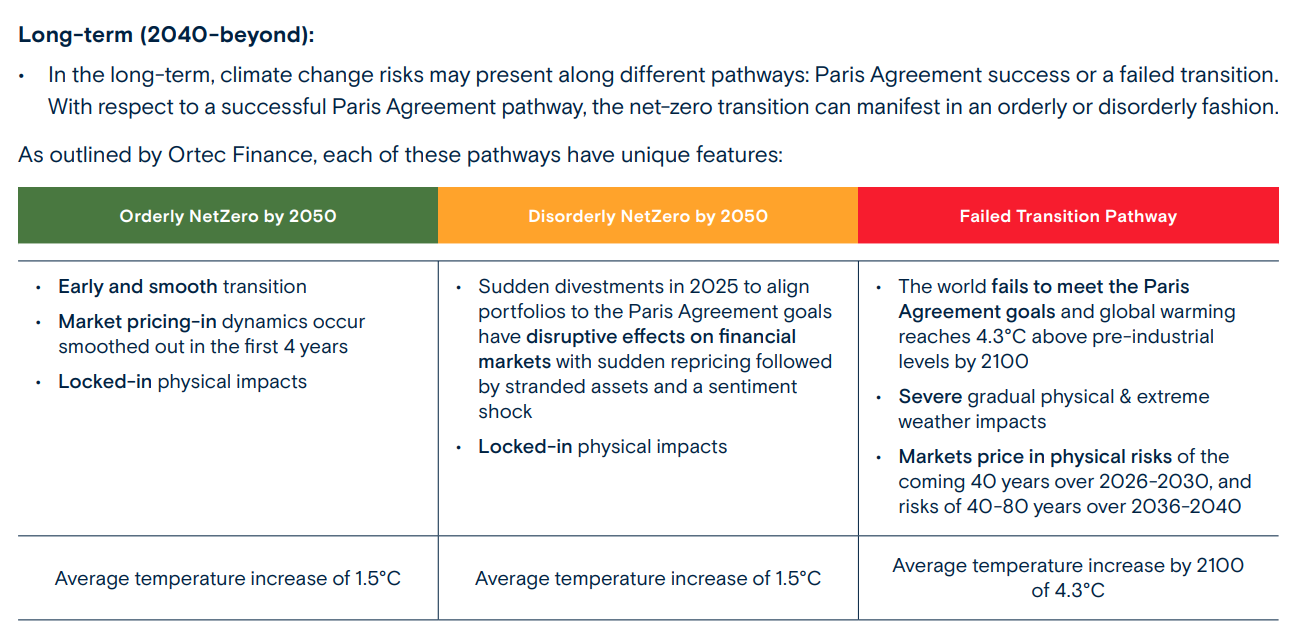

Climate Scenario Analysis

PSP partnered with Ortec Finance to consider three plausible climate pathways and their potential impacts to the PSP Investments portfolio, including two 1.5°C pathways (orderly and disorderly) and a “failed transition pathway” in which global average temperature increases by 4.3°C by 2100. The exercise captures both direct and indirect impacts in the scenarios employed (TCFD Report, p.4). It’s a significant improvement over PSP’s scenario analysis approach in 2021 and previous years (p.20), which assessed 2°C, 3°C, and 4°C scenarios (TCFD p.7).

Image: PSP Investments’ Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. (November 2022). P.7.

As a result of this process, PSP acknowledges “it is possible that investors have underestimated the short-term impacts of climate change in their financial modelling and projections” (TCFD Report, p.5). PSP also expects regulators to take more stringent climate action, and acknowledges that “carbon intensive investments may face increasingly strict regulatory requirements, eroding their capacity to generate future returns, hence the risk of lower valuations” (TCFD Report, p.5).

PSP’s scenario analysis finds that the failed transition scenario results in lower returns relative to the orderly net-zero transition scenario, due to climate change causing increased physical risks, higher inflation, greater supply chain risks, transportation challenges, and climate change’s acceleration of other sustainability risks that threaten livelihoods such as biodiversity loss, food security, energy and water shortages, and associated geopolitical tensions that “could result in a challenging environment for PSP Investments to achieve long-term positive returns” (TCFD Report, p.6).

Alarmingly, PSP concludes that its scenario analysis “has confirmed the resilience of PSP Investments’ Total Fund Strategy under many different future climate scenarios, including an orderly or disorderly, and failed net-zero scenario by 2050” and that “our policy portfolio would still achieve better relative performance compared to its reference portfolio” in a failed net-zero scenario (TCFD Report, p.7). This is highly unlikely. It is dismaying that PSP believes its portfolio could be resilient in a world that warms by 4.3°C, as this demonstrates a poor understanding of the science of climate change. It is difficult to imagine how any of PSP’s beneficiaries could reasonably expect retirement security, or a safe climate to retire into, in this or any other scenario where global heating averages exceed even the well-below-2°C guardrail enshrined in the Paris Agreement. PSP should seek scenarios which accurately reflect the latest scientific assumptions on warming risk for ecosystem, societal, and financial stability. PSP is obligated to use its influence, asset management and stewardship to accelerate the energy transition to prevent these harms from occurring, as it has begun to acknowledge (TCFD Report, p.8):

“In general, for all climate scenarios considered, investors should expect lower returns as compared to a world in which systemic climate change does not exist given that both physical and transition risk are likely not fully “priced-in” by financial market participants. However, a net zero transition scenario – even a disorderly one – enables global economies to stabilize once the transition has been completed. This demonstrates the need for investors to actively engage with companies and sovereigns to develop credible transition plans.”